Extract: Heat – Life and Death on a Scorched Planet by Jeff Goodell

When heat comes, it’s invisible.

It doesn’t bend tree branches or blow hair across your face to let you know it’s arrived. The ground doesn’t shake. It just surrounds you and works on you in ways that you can’t anticipate or control. You sweat. Your heart races. You’re thirsty. Your vision blurs. The sun feels like the barrel of a gun pointed at you. Plants look like they’re crying. Birds vanish from the sky and take refuge in deep shade. Cars are untouchable. Colors fade. The air smells burned. You can imagine fire even before you see it.

In the summer of 2021, weathercasters in the Pacific Northwest warned people that a heat wave was on the way. Workers in Washington’s Yakima Valley were summoned to cherry orchards at 1 a.m. so the ripe fruit could be picked before it turned to mush. Air-conditioning contractors were deluged with calls. Electric fans sold out at Home Depot and Lowe’s. The Red Cross activated its heat alert network, blasting out warnings to people to drink water and check on family and friends who lived alone. Libraries and churches set up cooling centers for the homeless or anyone who needed refuge.

Nevertheless, the heat hit with a force that few people anticipated. The Pacific Northwest, after all, has long been seen as a climate refuge. It was the place you moved to if you wanted to live somewhere that was “safe” from climate change.

SPECIAL OFFER

To celebrate the release of Heat, Black Inc Books is offering a special deal to Australia Institute supporters.

Order ‘Heat’ today for $30.99 + shipping

Enter code: HEAT2023 at the check-out

There are beaches and lakes and stately trees and volcanic soil where anything grows, from blueberries to boxwood to grapes that are crushed into world-class Pinot Noir. There are glaciers in the Cascades and lush temperate rain forests in Olympic National Park and more than a few fragments left of the Edenic paradise that pulled so many settlers over the Oregon Trail.

In the 1970s, Steve Jobs picked apples on a farm in the region and loved it so much he named a computer company after it. Heat wave? No big deal. This was not Phoenix, where heat owns the city. Or New Delhi, where heat is both a goddess and a demon. In the Pacific Northwest that summer, everyone might have known the heat was coming, but nobody thought it would be a searing, ghostly force that would melt asphalt and kill loved ones and force a new reckoning with the world they live in.

The heat wave had been born over the Pacific a week or so earlier. Atmospheric waves wobbled across the Northern Hemisphere, creating a high-pressure lid that allowed heat radiating up from the ocean to gather beneath it. As this pile of heat drifted to the coast, it grew quickly in size and intensity, creating what scientists called a heat dome. In a twenty-four-hour period, the temperature in downtown Portland jumped from 25 degrees to 45 degrees, the hottest temperature in 147 years of observations. Suddenly, the ferny salamander-land of the Northwest felt like the hard-baked steel and sand of Dubai.

Ice, nature’s most exquisite thermometer, registered the heat first. The last of the winter snow in the Cascades vanished from shady hollows in the forests and atop the glaciers near the peaks. With the protective snowpack gone, the blue glacial ice itself began to melt, rushing down streambeds and canyons in a swirl of silty gray water, carrying ancient sediment from before the fossil fuel age, before books, before the pyramids. The rush of meltwater flooded roads and towns as it rolled down to the rivers and out to the sea.

In streams and rivers, migrating salmon immediately sensed the changes in water temperature. They had spent three or four years in the cold, salty Pacific and now were swimming upstream in freshwater back to where they were born to lay eggs and begin the cycle anew. The salmon’s journey is one of the great wonders of nature. But it is also a fragile one. Warm runoff in the rivers — shallow water can heat up quickly as it flows down out of the mountains — made it difficult for the struggling salmon to breathe. Their iridescent silvery skin broke out in red lesions. Cottony puffs of fungus grew on their backs. Some escaped to cooler tributaries. But tens of thousands of others, exhausted and suffocating and literally disintegrating in the warmth, became meals for other fish or washed up on the riverbanks, where they were picked apart by racoons and eagles.

In the mountains and valleys, every plant and tree was assaulted by the heat, rooted in place and unable to move, creators of shade that were themselves unable to seek refuge. As the temperature rose, they struggled with the heat just as humans do, trying to preserve water while the sun and the heat sucked it out of the soil and the flesh of their leaves and trunks. All across the Pacific Northwest there was a great clenching as the plants closed the pores on the undersides of their leaves, in effect holding their breath, hoping the heat would pass quickly.

Blackberry and blueberry plants drank the moisture out of their own fruit, leaving it dry and withered on the stalk. On broadleaf trees like ash and maple, leaves brittled and curled. As temperatures rose, some of the most sun-exposed trees opened their pores, desperately trying to cool off by sweating. Their roots worked to pull water out of the dry soil, but instead sucked air bubbles into the veins that ran up their trunks, causing them to rupture. If you’d had the right kind of microphone, scientists say, you could have heard the trees screaming.

For some animals, however, these were good times. Caterpillars basked in the heat to kill pathogens in their bodies. Maggots hatched in the mouths of the dead salmon on the riverbanks. For pine bark beetles, an invasive species that is decimating western forests, the heat was like guzzling Red Bull. Their metabolism revved up, their appetite grew, and they moved like a marauding army through thousand-acre stands of Jeffrey pines.

In the cities and suburbs, air-conditioning units whirred. Overloaded power lines hummed and sagged. Sirens wailed and hospital emergency rooms were crowded with panting, red-faced people. Desperate to lower their body temperatures as quickly as possible, doctors filled body bags with ice and zipped them inside.

But as June came and went and summer turned to fall, life went back to normal, and the memory of the heat wave faded, as memories of heat waves always do, until they become like the fleeting images of a nightmare you’re not quite sure you had. Or a future you don’t want to imagine.

The last time the Earth was hotter than it is today was at least 125,000 years ago, long before anything that resembled human civilization appeared. Since 1970, the Earth’s temperature has spiked faster than in any comparable forty-year period in recorded history.

The eight years between 2015 and 2022 were the hottest on record. In 2022, 850 million people lived in regions that experienced all-time high temperatures. Globally, killer heat waves are becoming longer, hotter, and more frequent. One recent study found that a heat wave like the one that cooked the Pacific Northwest is 150 times more likely today than it was before we began loading the atmosphere with CO2 at the beginning of the industrial age.

The ocean, which hundreds of millions of people depend on for their food supply and which has a big influence on weather, was the hottest ever recorded in 2022. Even Antarctica, the coldest place on Earth, is not immune. In March of 2022, a heat wave invaded the ice-bound continent, pushing temperatures 30 degrees—30 degrees!— above normal.

Extreme heat is remaking our planet into one in which large swaths may become inhospitable to human life.

One recent study projected that over the next fifty years, one to three billion people will be left outside the climate conditions that gave rise to civilization over the last six thousand years. Even if we transition fairly quickly to clean energy, half of the world’s human population will be exposed to life-threatening combinations of heat and humidity by 2100.

Temperatures in parts of the world could rise so high that just stepping outside for a few hours, another study warned, “will result in death even for the fittest of humans.”

Life on Earth is like a finely calibrated machine, one that has been built by evolution to work very well within its design parameters. Heat breaks that machine in a fundamental way, disrupting how cells function, how proteins unfold, how molecules move.

Yes, some organisms can thrive in higher temperatures than others. Roadrunners do better than blue jays. Silver Saharan ants run across superhot desert sands that would kill other insects instantly. Microbes live in 70-degree hot springs in Yellowstone National Park. A thirty-year-old triathlete can handle a 40-degree day better than a seventy-year-old man with heart disease. And yes, we humans are remarkable creatures with a tremendous capacity to adapt and adjust to a rapidly changing world.

But extreme heat is a force beyond anything we have reckoned with before. It may be a human creation, but it is godlike in its power and prophecy. Because all living things share one simple fate: if the temperature they’re used to—what scientists sometimes call their Goldilocks Zone— rises too far, too fast, they die.

This is an extract from Heat: Life and Death on a Scorched Planet by Jeff Goodell, published by Black Inc Books.

‘This searing plea for a better, fairer and cooler future should be read by anyone with skin in the game – which is every single one of us.‘—NAOMI KLEIN

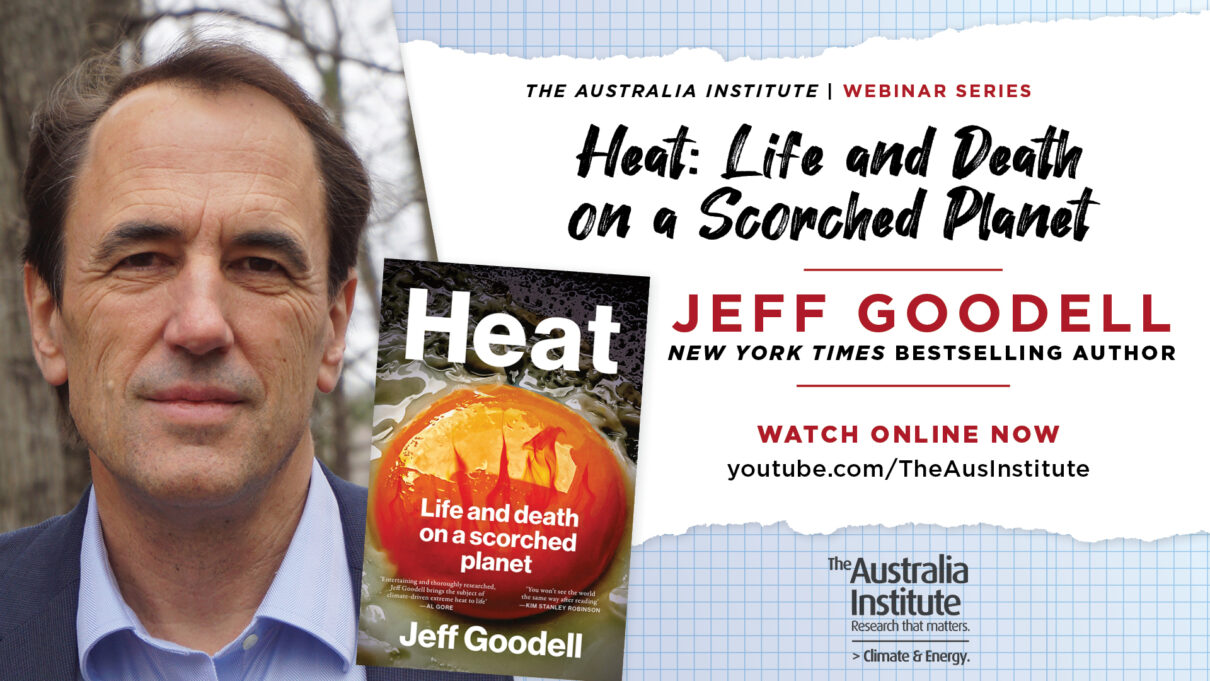

Watch our webinar with Jeff Goodell, discussing his new book: Heat: Life and Death on a Scorched Planet

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Heat: Life and Death on a Scorched Planet with Jeff Goodell | Summer Series

Our summer podcast series brings you some of the best conversations from our webinars and live events in 2023. Extreme heat is the most direct and deadly consequence of our hellbent consumption of fossil fuels. It is a first order threat that drives all other impacts of the climate crisis. And as the temperature rises,

The Issues That Will Shape 2024 | Between the Lines

The Wrap with Richard Denniss Happy New Year! While it’s only mid-January, 2024 is already off to a big start. US bookmakers have Donald Trump as favourite for the next presidency, Australia is getting drawn into US foreign policy in the Middle East, domestic debate about the $320 billion Stage 3 tax cuts is heating

Extreme heat fans flames of inequality

New research from The Australia Institute shows that older, sicker and lower-income Australians are at greater risk during heatwaves (days over 35° Celsius).