Corporate profits increase inflation | Fact Sheet

The prices of many goods and services have increased dramatically across Australia since 2021. This has resulted in hardship for many households—along with $100 billion in increased profits for major companies. These corporate profits have been a key factor driving inflation.

How do profits drive inflation?

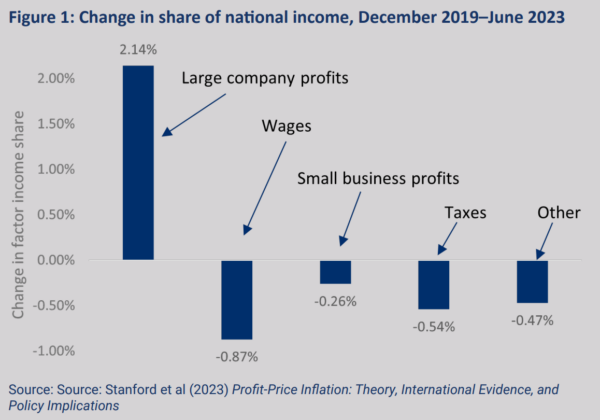

From December 2019 to June 2023, inflation in Australia rose faster than it has in 30 years. Over this time, the share of national income going to corporate profits also increased substantially.

At the same time, the share going to wages and small businesses declined.

The profits made by large corporations during this time are huge: some $100 billion over and above their pre-pandemic profit margins.

According to Australia Institute research, these rising profits made up more than half of the inflation above the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA)’s target range of 2% to 3%.

The link between profits and inflation in Australia was replicated in research by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), headed by former Liberal Finance Minister Mathias Cormann.

Why have big companies been able to increase profits?

The impacts of the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine increased costs globally. Businesses all over the world increased their prices to cover these increases in costs.

However, many businesses used this opportunity to raise their prices by more than their increased costs.

This allowed them to increase their profits.

Even after the impacts of the pandemic and Russian invasion have receded, some businesses have kept prices—and profits—high. The profit margins of Coles and Woolworths, for example, are much higher now than before the pandemic.

Australia is particularly vulnerable to profit-influenced inflation because many Australian industries are dominated by a few large companies—two supermarkets, two airlines, four banks, and so on.

In such industries, companies try not to compete on price.

Instead, they prefer to compete on advertising and loyalty programs, or with other tactics like trying to dominate store locations and airport space, etc.

A recent in-depth study by Prof Allan Fels, the former chief of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, found that a lack of competition across the economy enables “businesses to engage in exploitative pricing practices.”

Among Fels’ recommendations was a Prices Commission to review high prices caused by a lack of competition.

Does this increase interest rates?

Yes.

The RBA aims to keep annual price rises between 2% to 3%. When inflation goes above 3% the RBA usually raises interest rates. It has increased interest rates 13 times since 2022—the most for over 30 years.

The theory behind the RBA’s interest rate increases is that higher interest rates will increase the cost of mortgages and rents for most households. With less money to spend, the RBA hopes that households will buy fewer things, decreasing demand and bringing prices and wages down.

However, higher interest rates only work to reduce inflation if high household spending is causing the price rises in the first place. If the inflation has other causes—corporate profits, a pandemic, and overseas wars—increasing interest rates simply increases housing costs, reduces investment and risks sending the Australian economy into recession.

What can be done?

The RBA’s current approach to inflation serves only to punish those people who are already suffering most from the effects of corporate profiteering.

First and foremost, therefore, the RBA should reduce interest rates, and stop trying to use interest rate increases to reduce profit-driven inflation.

Policies that would address this form of inflation include:

- Implementing reforms to increase competition in industries dominated by a few large companies. These could include the reforms suggested in the Fels report, such as ‘divestiture powers’, which allow uncompetitive companies and industries to be broken up. Such powers are common internationally; famously, the United States has broken up uncompetitive oil companies.

- Implementing price controls for important parts of the economy—such as rents, energy, and essential goods and services—in times of emergency.

- Assisting in the electrification of homes to reduce dependency on gas, which is both costly and emissions-intensive.

- Imposing super profit taxes, especially in uncompetitive industries such as banking, energy, wholesale and retail sectors. The extra revenue could be used to provide cheaper services or compensate those on low-middle incomes hurt the most by rising prices.

Related documents

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

The debate about inflation, interest rates, and the cost of living is broken.

Spreading fear about inflation not falling fast enough distorts the true picture

Would you like a recession with that? New Zealand shows the danger of high interest rates

New Zealand’s central bank raised interest rates more than Australia and went into a recession – twice.

‘Sticky’ inflation is not falling – but it’s not rising, either. Why should that mean another RBA rate hike?

The latest inflation figures released on Wednesday showed that inflation is “sticky” and is no longer falling at the pace it was earlier this year.